Scala variance and blood groups

One of the topics that is often glossed over in the first pass of learning Scala is the topic of variance. Variance is the rules that determine how the inheritance relationship between two types is transferred to objects parameterised by those types. We look at the rules regarding blood donation for the different blood groups as an analogy for variance.

Let’s say we have two classes:

class Foo

class Bar extends Foo

This means that Bar is also a Foo. Can we say the List[Bar] is also a List[Foo]? It turns out that we can. This is called covariance.

We say a List is covariant, and in scala it is denoted as follows:

class List[+T]

The dual concept of covariance is contravariance. It is harder to find examples of contravariance in the standard library, but it is nonethelesss an essential concept.

A common example given is T => R which is covariant in the return type and contravariant in the input type.

trait Function[-T, +R]

If a parametrised object is neither contravariant, not covariant, it is said to be invariant.

Variance is often explained in terms of where it breaks down. The usual example is given is a Java array, which is covariant, but a run time exception is thrown if you use it in a non-covariant way.

Instead of this, there is a real life example that illustrates both contravariance and covariance, and as any doctor knows, can have deadly consequences if you get it wrong!

Blood Types

The main classification of of blood type is the ABO system. The A, B and O classification is determined by the presence (or absence) of certain molecular structures in the blood cell called antigens. In the case of group A, the A antigen is present, for group B, the antigen B is present, for AB both A and B are present, and for O, neither are present.

However it is actually the antibodies present in the blood plasma that actually determine the inheritance relationship. A type blood contains antibodies against B antigens, B type blood contains antigens against A antigens, and O blood contains antibodies against A and B antigens.

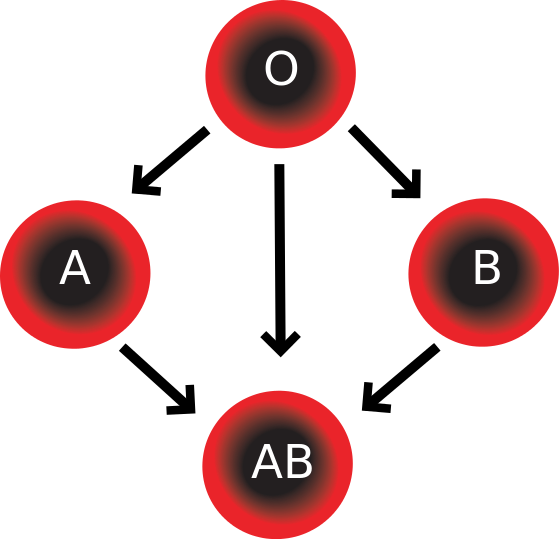

These antibodies lead to the compatibility chart:

When discussing class inheritance we proceed according to the Liskov Substitution Principle: A subtype can always be substituted in cases where it’s parent type is expected. Accordingly, type AB is actually the supertype of the other blood types, as we can substitute any of the other types when type AB is expected.

This leads to an inheritance heirarchy that is the opposite of the blood compatibility chart.

We can express this inheritance relationship in Scala code as:

object BloodGroups {

trait AB

trait A extends AB

trait B extends AB

trait O extends A with B

}

It took me a little thinking to convince myself that this was the natural heirarchy for blood groups, at least from the point of view of blood donation, as my original suspicion was that it was the other way around, with O being the base class for all others. There are however, other ways of viewing things, in which O would naturally be the base class. The way we model objects does depend on the problem we are trying to solve.

Donors and Recipients

We ask the question how the inheritance relationship between blood groups extends to the act of giving and receiving blood. For example, considering that O is a subtype of A, is a donor of type O a donor of type A? And is a recipient of type O a recipient of type A?

To answer these questions, consider the edge cases. O is known as the universal donor, as they can give to anyone, but can only recieve from another person of type O. On the other hand, AB is the universal recipient, but their blood is only useful to another of type AB. This suggests the following covariance relationship:

- Donors are covariant. A donor of type

Tis a donor to all its subtypes. - Recipients are contravariant. A recipient of type

Tis a recipient of all its supertypes.

We can express these contracts as Scala traits:

trait Donor[+T] {

def give(): T

}

trait Recipient[-T] {

def receive(blood: T)

}

These concepts apply in general in Scala, and other languages that suppport variance.

For example why is a List covariant? It turns out that any immutable data structure only has methods that return values, or other data structures. In this sense they perform the role of donors.

Contravariance, on the other hand, is associated with receiving. Returning to the example Function[-T, +R], a function receives a parameter and emits a result. Receiving or accepting a parameter is contravariant in nature, as accepting on object of type T, implies the ability to accept any parameter of type U, where U is a more specialised type than T.

These rules apply as long as the Liskov Substitution Principle is adhered to throughout.