Kubernetes operators for resource management

In this post we discuss Kubernetes and its emergence as a tool of choice for infrastructure orchestration. We specifically focus on operators, a pattern for extending the Kubernetes to manage arbitrary custom resources, and discuss how they enable infrastructure management of complex hybrid environments. We look at how to implement operators in a robust, generic way for any resource that itself has a management API consisting of CRUD (create, read, update and delete) operations, and introduce a library created to enable this.

I consider myself primarily a backend and data engineer, and have over time also picked up a bit of front end and mobile experience, specifically in React. Over time there has been a trend to a “build it, run it, own it” way of thinking in which developers also have greater operational responsibilities, rather than just throwing code over the fence for ops people to pick up. As part of this, “full stack” expands to include devops, in which infrastructure is defined and provisioned in code. Naturally it was only a question of time before an infrastructure tool arrived that developers would take to, and for me Kubernetes is the first such framework or platform.

Kubernetes started off as a platform for container orchestration. It is declarative in nature - you specify what the desired state the system infrastructure should be, and it attempts to configure the system accordingly. This is a robust pattern. It focuses on the question “How many pods are running?” or “Is this service up?”, rather than questions such as “Did this pod start or stop?” or “Did the service go down?”. This is referred to as level triggering in contrast to edge triggering. Kubernetes continually monitors this and attempts to self heal and is successfully able to do so in numerous cases.

A subsequent addition to Kubernetes are custom resources. With custom resources you can add an additional layer of customisation to your container deployments, including to manage resources that have nothing to do with containers. This expands the applicability of Kubernetes beyond container orchestration to far more general infrastructure workflows. Custom resources look, feel and behave like native Kubernetes resources, and indeed many later extensions to Kubernetes itself are implemented as custom resources.

Most complex environments, particularly those running on the cloud, are hybrid deployments, consisting of applications running in containers, but also talking to databases and other services running in the cloud. In addition to this, there may be dependencies on other platform-as-a-service (PaaS) products provided by 3rd party providers. An important observation we leverage later is that almost all these services, whether cloud services or 3rd party PaaS’s, can be administered by CRUD operations (typically a REST API).

A fundamental requirement of devops is full automation of all infrastructure provisioning from code. The “classic” way of achieving this would be to handle the container orchestration in Kubernetes, but use other tools to automate the rest of the environment. With Kubernetes custom resources, it is possible to bring all these different types of infrastructure under a single Kubernetes umbrella, enabling management of everything from one place in a standardised and streamlined way, throughout the full infrastructure lifecycle.

All Kubernetes resources are described in definition files called manifests that describe the desired state of the system. For any Kubernetes object, the manifest consists of 3 main sections:

- A

specsection - this describes the intended state of the object or resource the manifest refers to - A

statussection - this consists of status information describe the current state of the resource - A

metasection - contains an assortment of metadata about the resource

Kubernetes attempts to modify the system to get actual state to match this desired state in what is referred to as a reconciliation loop. The code that gets called in the reconciliation loop is called a controller.

Controllers will typically respond to changes in the spec, and update the status and at times, the meta sections.

The controller should never update the spec section. This is normally only done by the user, using kubectl,

the Kubernetes CLI, or via something like a gitops process using a tool like Flux.

Frameworks and reconcilers

Implementing a Kubernetes resource is a two part process, which is collective referred to as the operator pattern:

- A custom resource definition (CRD), which is essentially the schema for the custom resource’s manifest.

- A custom controller which handles the implementation logic of the custom resource.

The are currently two main operator frameworks, the Operator SDK, and Kubebuilder. These frameworks simplify the process of creating an operator, by providing a high level abstraction over the Kubernetes extension layer. They are both written in Golang.

I am somewhat more familiar with the Kubebuilder framework, having encountered it on various projects.

What Kubebuilder and the Operator SDK for you (amongst other things) is:

- Scaffold a Go operator project

- Scaffold APIs for new resource types

- Provide the mechanism to express your manifests as Go

structs and converts these to CRDs - Provide a test mechanism that enables you to test your controllers without requiring a K8s cluster. and being reasonably opinionated on how it does all this, it saves you a lot of work.

However, what is is not in the least bit opinionated about, and rightly so, is the implementation of your custom controller, or probably more aptly named, custom reconciler.

This is the one method you need to implement, and it’s a surprising simple one:

type Reconciler interface {

Reconcile(Request) (Result, error)

}

Even the Request and the Result types are very simple, they are just structs,

the Request consisting of a name and a namespace, and the Result with some simple details on whether it should reconcile next, and when.

However as is frequently the case, simple is not necessarily easy (and vice versa!). Implementing robust operators is not that easy. And if you get your operators wrong, they can become the weak link in your infrastructure setup, your cluster moves from self healing to self harming, and you give Kubernetes an undeserved bad name!

Indeed behind the apparent simplicity of a reconiler is a minefield of complexity, especially when dealing with real world use cases with deviations from the happy path at any point.

The root cause of this complexity is the interface itself. Simple interfaces are pure interfaces

(in the functional programming sense) with well defined and isolated effects.

This Reconciler interface is anything but,

as neither the input not the output types convey any real useful information.

There are other challenges we have to deal with when implementing a custom controller. For example, we are generally not trying to stand up one service at a time, rather a suite of services, with ordering dependencies between them. For example, in Azure, we may require that the resource group is provisioned before we create a SQL server in this resource group.

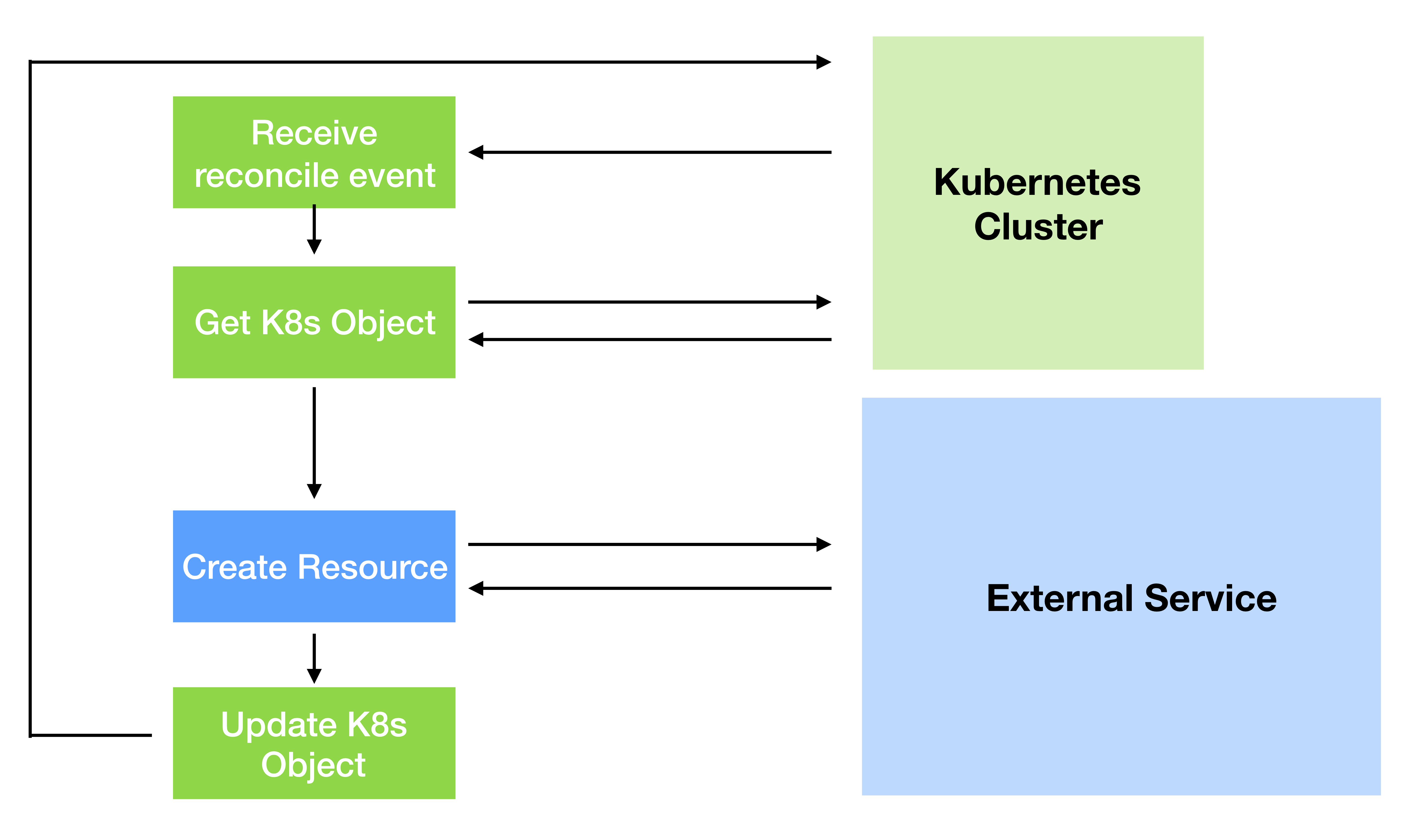

The typical workflow in the reconcile loop is the following pseudocode:

type Reconciler interface {

Reconcile(req Request) (Result, error) {

// get the Kubernetes object (i.e. the manifest)

kubeObject := KubeClient.Get(ctx, req.NamespacedName)

// apply some effect based on the object Spec (e.g. spin up a database, provision some cloud infrastructure)

externalResult := ApplyExternalEffect(kubeObject)

// modify kubeObject based on what we know so far

updatedObject := UpdateK8sObject(externalResult, kubeObject)

// save this updated object/manifest back to Kubernetes

KubeClient.Update(ctx, updatedObject)

// decide when to reconcile next etc and return

return GetReconcileResult(externalResult, updatedObject);

}

}

The reconciler has do something to be useful, as they don’t return anything useful. This happens in ApplyExternalEffect.

Note that these effects can be synchronous or asynchronous. When dealing with infrastructure, things can take a while, and you don’t want to block on them finishing. And in every case things can fail or timeout, and this needs to be dealt with correctly.

Implementing this method successfully requires code of two types:

- Code that interacts with Kubernetes (even if that means updating the manifest)

- Code that interacts with the outside world, doing whatever the operator is meant to do.

Through working on a a project to build operators for Azure services, I got the opportunity to investigate the common workings of operators for a variety of resources. It became clear that for a general class of use cases, the code that interacts with Kubernetes is, or at least can be, always pretty much the same.

The use case is operators that expose resources to Kubernetes that themselves are managed via CRUD (create, read, update and delete) operations, typically a REST API. These CRUD operations can be synchronous or asynchronous. Almost all cloud services have a REST API management layer. The use case referred to is perhaps the most compelling use case for operators in the first place. In addition, many third party platforms running in the cloud that provide specific services are have REST API management interfaces for provisioning their services.

To achieve this we identify the sort of interactions that are common to any such implementation.

The happy path is quite straightforward, ad generally looks like this:

However the robust real world implementation that handles the full lifecycle is much more involved. We want our operators to be robust enough to deal with missing dependencies, handle errors that may occur interacting with external resources, provide useful information about what went wrong, and be able to recover their state once the underlying cause is resolved.

There are quite a few edge cases that have to be dealt with. For example, what if we try to create an external resource and that resource is already present? Do we take ownership of it? Do we delete it when the Kubernetes resource is deleted.

We are generally not able to get by with a single operator, but normally a suite of dependent operators to cover a set of related resources. There is enough complexity in a robust implementation that we wouldn’t want to repeat everything for each resource. There is a need to generify.

Operator architecture principles

To solve the dependency problem cleanly, as well as arrive at clean overall design, it helps to take a step back and clarify some architectural principles that enable the design of a well behaved suite of operators. Our high level architecture is around central principle that each operator represents a single resource, and manages it throughout its lifecycle. It has this one job and does it well. So much so that it is relied upon by every other resource in the Kubernetes cluster as a single source of truth about this resource.

-

An operator manages a single custom resource.

A single one-to-one mapping between K8s custom resources and external managed resources helps to arrive at a clean design and ensure separation of concerns.

-

Operators verify the state of the external resource they manage, and repeat the reconcile loop until the resource is a state ready for consumption.

An operator should be treated as the single source of truth within the K8s cluster about the external resource it manages. They are expected to do this job well as they may be relied upon by other components for this purpose as well as for their own reconciliation.

-

Controllers verify that dependencies are satisfied by fetching and inspecting the K8s custom resource for each dependency.

An operator never needs to interact directly with the custom resource its dependency manages. For example, the SQL server K8s controller never interacts with the resource group management API.

It only interacts (typically in a read only way) with the resource group K8s resource, and in general only needs to know whether or not the resource is in a

Succeededstate. -

If any of the K8s dependencies are not satisfied the operator reattempts some moments later by requeuing the reconcile, and repeats this indefinitely.

A missing dependency is not treated as a failure condition. It simply waits for this dependency to become available by requeuing.

-

Unmanaged resources are assumed to be present when required.

It is preferable that all resources are managed by operators, but in certain cases, there may be an operator available.

For example, we may require access to a storage bucket that is not managed by an operator on the cluster.

These dependencies should be assumed to be always present when required.

If provisioning fails because an unmanaged resource is not present, this a failure state (as opposed to a missing dependency on a managed resource).

This simplifying assumption:

- Removes the need for duplicating status logic (managed and unmanaged)

- Allows for better encapsulation, as external resources are only interacted with from a single operator.

-

Deletion of external resources is idempotent (in nature at least).

If you delete a resource group in Azure, any of the resource groups that it contains are deleted with it.

If the resource group is managed by a K8s operator, and the K8s custom resource that represents it has children, the finalizer for the children also gets invoked. When this happens, the Azure resource it manages may already have been deleted, or be in the process of being deleted (deletion of Azure resources can be very time consuming).

If a delete request fails with a 404 (not found) error, this is not treated as a failure.

The state machine operator model

Without needing to know anything about a CRUD resource, there are only so many states it can be in. Any resource starts off as missing, then it is created, potentially updated, and eventually deleted.

These states are given by the following Go enum, which is stored as a field in the status section of the object’s manifest.

type ReconcileState string

const (

Pending ReconcileState = "Pending"

Creating ReconcileState = "Creating"

Updating ReconcileState = "Updating"

Verifying ReconcileState = "Verifying"

Completing ReconcileState = "Completing"

Succeeded ReconcileState = "Succeeded"

Recreating ReconcileState = "Recreating"

Failed ReconcileState = "Failed"

Terminating ReconcileState = "Terminating"

)

Some of these have an obvious interpretation on inspection. Others may need further elaboration.

For every exogenous change to the manifest (usually via kubectl apply or via the Kubernetes API) the reconcile loop runs

through several times. Each time we run through the loop the following may happen:

- Verification that certain conditions are satisfied

- An interaction with the CRUD management API

- An update the

ReconcileStatein the manifest - A response with details on the next reconcile

This process continues until a steady state is realised.

The steady terminal state would generally be either Succeeded or Failed. We could stop there,

though we need not necessarily - we can optionally continue running the reconcile loop periodically to

detect for changes to external state to provide a monitoring capability (e.g. to detect downtime).

For each of the ReconcileState states that the operator may be in, there is a corresponding CRUD operation.

For example if the current ReconcileState is Creating, the obvious corresponding CRUD operation is the create operation.

For each of the three mutating CRUD operations, though the external effect may be arbitrary,

there is a finite set of possible outcomes on the ReconcileState. For example, for a create operation,

there are only three possible outcomes - either it succeeds, it fails, or (in the asynchronous case) it is incomplete,

and we have to return later to check what the result is.

This key idea is what we take advantage of to provide a generic abstraction: It doesn’t matter what the operation is, the effect it might have, or the cause of the error if there is one - this set of possible outcomes on the reconciler is still one of these.

For example, the create result can be represented by the following enum:

type CreateResult string

const (

AwaitingVerification CreateResult = "AwaitingVerification"

Succeeded CreateResult = "Succeeded"

Error CreateResult = "Error"

)

Then given a result from one of these operations, it should be clear what the next transition of ReconcileState is.

E.g. the above example, if the CreateResult is AwaitingVerification, the next value of ReconcileState is Verifying.

One can thus think of an operator as a finite state machine. Each time it loops through the reconciler, the state is updated, and an effect is produced.

Operator implementation

We start with the question “What is the simplest interface you could provide to a developer implementing an operator?”. Let’s assume they are familiar with the API of the external resource, but know very little about Kubernetes.

As mentioned before, the interactions with Kubernetes are generic, and the interaction with the external resource is specific to that resource.

With this in mind, we minimise the direct interactions with Kubernetes by provided the following interface:

type ResourceManager interface {

// Creates an external resource, though it doesn't verify the readiness for consumption

Create(ResourceSpec) (CreateResult, error)

// Updates an external resource

Update(ResourceSpec) (UpdateResult, error)

// Verifies the state of the external resource

Verify(ResourceSpec) (VerifyResult, error)

// Deletes external resource

Delete(ResourceSpec) (DeleteResult, error)

}

where ResourceSpec consists of the manifests for the object as well as its dependencies:

type ResourceSpec struct {

Instance runtime.Object

Dependencies map[NamespacedName]runtime.Object

}

and the CreateResult, UpdateResult, VerifyResult and DeleteResult are simply enums.

The UpdateResult enum is the same as the CreateResult.

The Verify method is probably the most interesting. We need to be able to distinguish several different cases:

- The external resource is missing

- The resource is present, but its current state is not the desired state. Either:

- A relatively minor change is required and it can be updated

- It needs to be deleted and recreated

- The resource is being created asynchronously, so it present in some form, but this process is still in progress

- The resource has successfully created and is ready for consumption

- Some error happened along the way, and the resource failed to create or update

- The resource is busy being deleted, but this has not completed

These states can be represented by the VerifyResult enum:

type VerifyResult string

const (

VerifyResultMissing VerifyResult = "Missing"

VerifyResultRecreateRequired VerifyResult = "RecreateRequired"

VerifyResultUpdateRequired VerifyResult = "UpdateRequired"

VerifyResultInProgress VerifyResult = "InProgress"

VerifyResultReady VerifyResult = "Ready"

VerifyResultError VerifyResult = "Error"

VerifyResultDeleting VerifyResult = "Deleting"

)

Note that although not all states are always attainable for a given resource, this enum is general enough to cover the possible states for any resource managed by CRUD operations, sync or async, that Kubernetes might care about.

So given an implementation of the ResourceManager interface, it’s possible to implement the state transitions in the reconcile loop generically.

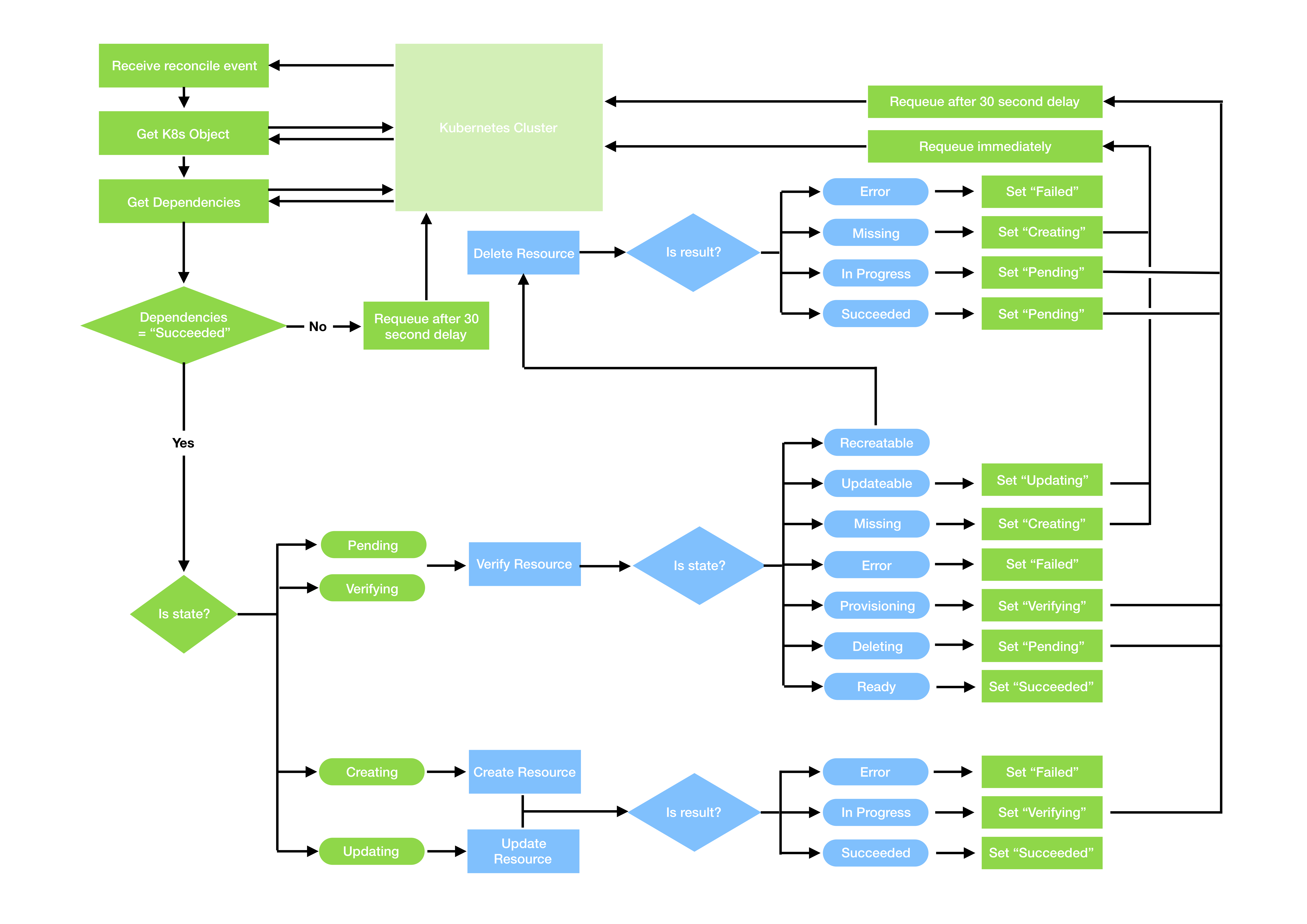

It may end up something like this:

The blue boxes represent the ResourceManager implementation, and the green boxes represent the reconciler loop logic.

Putting it all together

If you follow some of the above suggestions, you should be well on your way to implement a generic reconcile loop for managing CRUD resources.

However you don’t even have to, as an implementation is provided for you in Operatify, an open source project at https://github.com/operatify/operatify.

In the lifecycle diagram above, you implement the blue boxes, and Operatify implements the green boxes for you.

You start by using Kubebuilder to scaffold your operator, creating your manifest as a Go struct their way

It can create a controller for you but you don’t anything from need this controller except for the RBAC markers - e.g. if the kind is MyResource:

// +kubebuilder:rbac:groups=mygroup.my.domain,resources=myresources,verbs=get;list;watch;create;update;patch;delete

// +kubebuilder:rbac:groups=mygroup.my.domain,resources=myresources/status,verbs=get;update;patch

To create the controller you need to:

- Implement a

ResourceManagerto wrap the CRUD interactions with the external resource. This is the main part. - Implement a

DefinitionsManagerto declare the dependencies and provide some simple boilerplate conversions. - Wire it all together by creating a

GenericController.

You just need to understand the external resource API - it’s very straightforward from there.

Specific instructions are given in the Operatify repo.

Some finer details

If you take a look at the Operatify repo, you may notice that there are a few key differences with what is presented here. These are intentionally omitted here for the purposes of clarity.

It’s not possible to talk at length about all the nuances in this blog post, but some are some worthy of mention to give a general flavour:

Resource diffing and status

The quality of your operator ends up being as good as your ResourceManager implementation.

The more accurately you capture the state of your resource in these operations,

the more refined will be your operator.

One of the key touchpoints is the Verify method of the ResourceManager interface. For example,

one may ask, “what is the best way to determine whether the resource is invalid,

and if so, whether an update will suffice, or whether it needs to be recreated?”

There are several ways one could go about this.

One way is to fetch the external resource, inspect its properties, and compare those with the manifest’s spec.

This may not be possible in some cases though, as the original properties used to create the resource may not be exposed.

There are two other valid alternatives. The first is every time the Create or Update method returns successfully,

an [annotation-base-name]/last-applied-spec

annotation is saved with the Json representation of the spec that was used to create or update the resource.

One could diff against that. kubectl does something similar.

The other alternative is the Create, Update and Verify can also return an extra status payload return parameter.

This is an interface{}, so can be anything. The idea is this should be saved as a status field in the manifest.

The reconciler will not care about it, but will be passed back into the subsequent calls to Verify.

Neither of these alternatives cover the case where someone modifies the resource externally, but I believe that ops people should keep their hands off production resources that are managed by an operator - or at least know that they do this at their peril.

Locking down access control

Coming back to the edge case “what if we try to create an external resource and that resource is already present? Do we take ownership of it? Do we delete it when the Kubernetes resource is deleted.”

The reconciler recognises an annotation [annotation-base-name]/access-permissions, in which it recognises each one of the permissions, create, update and delete via the initial.

Read permission is implicit. For example "CD" is permission to create and delete, "CUD" is everything (the default if this annotation is not defined), and anything that doesn’t have these initials (e.g. "none")

is read-only permissions.

Read-only permission has a specific purpose - it allows one to assert the state of a dependent resource without updating it.

If for example the desired state for a resource is not satisfied,

and the Verify method returns VerifyResultUpdateRequired, but the update permission is not set,

it results in failure.

Delete works slightly different - if this permission is not set, it will simply not delete the external resource when the Kubernetes resource is delete.

However if the Verify method returns VerifyResultRecreateRequired and delete permission is not present, it will result in failure.

Implementing a handler upon success

Sometimes after creating or updating a resource, further interaction with Kubenetes is necessary.

For example an operator that provisions a database may need to create a Kubernetes secret with database credentials.

There a hook to invoke these interactions which gets called, if it is defined, after a successful create or update.

This the only instance where custom interactions with Kubernetes are necessary. This operation should be idempotent.

Conclusion

Operators provide a very useful mechanism for extending Kubernetes, and really help to unlock the full potential of Kubernetes as a end-to-end infrastructure management platform.

However they are not that easy to implement well. Hopefully some of the suggestions offered here may help to avoid some of the potential pitfalls.

The Operatify project may also be of particular interest to you if you are looking to implement an operator, or a suite of operators, for CRUD-managed infrastructure resources.