Free monads and event sourcing architecture

In this post we look at free monads, a widely applicable functional programming technique that is rapidly gaining traction amongst Scala developers, and show that they are ideally suited to implementing an event sourcing data architecture. We discuss some of the restrictions on a free monad API that are required for event sourcing to work optimally, and review some related best practices.

Since delving into free monads in recent times, they have become an ubiquitous pattern in our code base. It is a functional programming technique in which you describe the instructions that a program in a way that is completely separated from the execution of these instructions.

But hang on, doesn’t that sound like an interface in object oriented programming? Yes, there are similarities. But they are differences some pretty major differences, such as:

-

Free monads are closed under monadic operations, in the mathematical sense. Just like a vector space is closed under linear operations. This means that any set of monadic operations, such as maps, flatmaps as well as extension such as traverses can be performed on a free monad, and it still a free monad - it retains its essential nature. Monadic operations are by no means all-encompassing, but are often rich and expressive enough to represent a wide range of common use cases, and in particular capture the notion of sequential computation. So you can create an entire program that itself is also a free monad of the same type, without stepping out of the monad, in a way that will be illustrated below. You certainly can’t say anything like that about interfaces in OO!

-

Free monads are data. This comes with all the benefits of being data, such as easy serialisation, transformation and portability. They are sometimes referred to as a “program that describes a program”, but they could be described as “a data structure that represents a program that describes a program”.

Free monads are a somewhat difficult concept to get your head around, but they end up being simple to work with. This blog is not intended as a comprehensive description or tutorial on free monads. There are quite a few resources for that:- here is quite a nice gentle introduction for the uninitiated: http://perevillega.com/understanding-free-monads. There’s many excellent talks available online, and of course the red functional programming book is a classic and always to be recommended, and describes the pattern from first principles.

Instead, the aim of this post is to relate free monads to event sourcing, another well known and very worthwhile pattern. The principle of event sourcing relates to data storage and management. It suggests a different way of thinking about your data in which the current database state is not the fundamental source of truth, but the ordered sequence of events that were used to get it into this state. Databases are generally mutable, and their state is modified by create, update and delete operations (everything but the read in the so called CRUD operations). This sequence of events that describe these mutations are themselves immutable, and together constitute an append-only event log. Event sourcing is treating this event log as the source of truth, and the database as a derived projection or snapshot in time of this cumulative history.

There are numerous benefits to event sourcing, including but certainly not limited to:

- Audit trail - having a complete sequence of timestamped events enables you to review previous transactions and rewind your database state to any point in time to replicate historical state.

- Robustness - if there’s any failure in the database, or data is not committed or otherwise lost, you can fall back on the event log and try again, or restore from there.

- Migrations - data migrations can sometimes be very difficult, especially if it involves moving to an entirely different data model, and you need to keep the system running. Event sourcing simplifies this and dramatically diminishes the risk. The new database is just inflated by applying the events to the new data model or database instance. And it can be done in real time with no downtime, as you can carry on streaming the old events into the new data instance continuously, until you flick the switch over.

Event sourcing is a good fit for a microservices architecture, and creates options for how we decompose our system. For example if we have a module that indexes to elasticsearch, it could be set up as a separate module that subscribes to the event log. When we start to think about our system that way, the event log assumes central importance within our overall architecture.

Free monads and event sourcing are an excellent match. So much so, that after understanding the benefits of free monads, and following some of them to their natural conclusion, you could end up inventing event sourcing if it didn’t exist already.

A term that if often associated with event sourcing is CQRS (Command query responsibility segregation). That’s a complicated way of saying separating commands (create, update and delete operations) from queries (read operations). This concept is paramount for event sourcing to work. The implications of this are described in detail below.

Free monads enable you to simplify your thinking about a programming task. When creating a system, you consider the domain you are trying to model, and you come up with an instruction set to model that domain. In functional programming speak, that is often referred to as an algebra, I suppose for the closure reason given above. I’m going to take the liberty of borrowing Martin Fowler’s example for two reasons:

- It saves me having to concoct an example

- It gives a like-for-like basis to compare Free monad event sourcing with a conventional OO example.

I hope he doesn’t mind!

Accordingly, we could create a simple language or algebra from the following events:

- Departure: ship leaves a port

- Arrival: ship arrives at a port

- Load: cargo is loaded on a ship

- Unload: cargo is unloaded from a ship

Source code is in Scala as it’s the functional language I know, but I’m pretty sure it would all work the same in Haskell.

sealed trait ShipLocation

case object AtSea extends ShipLocation

case class InPort(place: PortCode) extends ShipLocation

sealed trait ShipOp[A]

object ShipOp {

// Commands

case class AddPort(name: String, code: PortCode) extends ShipOp[Unit]

case class AddShip(name: String, code: ShipCode) extends ShipOp[Unit]

case class Departure(ship: ShipCode, place: PortCode, time: DateTime) extends ShipOp[Boolean]

case class Arrival(ship: ShipCode, place: PortCode, time: DateTime) extends ShipOp[Boolean]

case class Load(ship: ShipCode, place: PortCode, time: DateTime) extends ShipOp[Unit]

case class Unload(ship: ShipCode, place: PortCode, time: DateTime) extends ShipOp[Unit]

// Queries

case class GetLocation(ship: ShipCode): extends ShipOp[Location]

}

Free monads have the type signature Free[F[_], A], where F is the “instruction set”, and in the case of this example, ShipOp. So we can define

type ShipFree[A] = Free[ShipOp, A]

and this ShipFree is a monad. Free[F[_], A] is available in functional programming libraries like scalaz and cats (which is what we are tending to use).

We then create a program that comprises instructions from the algebra:

val program: ShipFree[_] = for {

_ <- AddPlace("Los Angeles", PortCode.la).liftF

_ <- AddPlace("San Francisco", PortCode.sfo).liftF

_ <- AddShip("King Roy", ShipCode.kr).liftF

...

_ <- Departure(ShipCode.kr, PortCode.sf).liftF

...

_ <- Arrival(ShipCode.kr, PortCode.la).liftF

location <- GetLocation(ShipCode.kr)

} yield location

liftF is an extension method on the ShipOp instruction set that “lifts” a ShipOp instance into an instance of ShipFree.

Coming back the the vector space analogy, we can think of the ShipOp instruction set as a vector basis, the monadic operations are the linear operations and the free monad ShipFree is a vector space. Note that the entire sequence of operations that defines program is still itself a ShipFree monad, and this is what is meant by the closure property.

And finally, we need to create an interpreter, which is a natural transformation from the free monad to a monad type that handles the evaluation, like a scala Future or a scalaz or cats Task. Please consult the links above for more elaborate explanation. In the vector space analogy, a natural transformation would correspond to a linear transformation.

It is common to have more than one layer of interpreters, where layers represent different levels of abstraction within the system. For example, if you are using the doobie framework for data access to SQL databases, as we do, the interpreter may be a natural transformation ShipOp ~> ConnectionIO, and then a second interpreter layer, with transaction support, is provided by the doobie library. ConnectionIO is itself a free monad over the JDBC database operations.

So our interpreter may look like this:

object ShipOp2ConIO extends (ShipOp ~> ConnectionIO) {

override def apply[A](fa: ShipOp[A]): ConnectionIO[A] = fa match {

// commands

...

case AddShip(name, code) => insertShipDbQuery(name, code)

case Departure(ship, place, time) => addDepartureDbQuery(ship, place, time)

...

// queries

case GetLocation(ship) => getLocationDbQuery(ship)

...

}

}

Then running our program is simple. We just foldMap and pass in our interpreter to create a ConnectionIO for the entire sequence of database queries:

val locationIO = program.foldMap(ShipOp2ConIO)

and then let doobie do it’s thing (well explained in the book of doobie):

val locationTask = locationIO.transact(taskTransactor)

val location = locationTask.unsafeRun

Note that the program is pure functional code. Any side effects are relegated to the interpreter. In the above doobie example, this is further relegated to the final Task.unsafeRun, though this need not always be the case.

Adding event sourcing

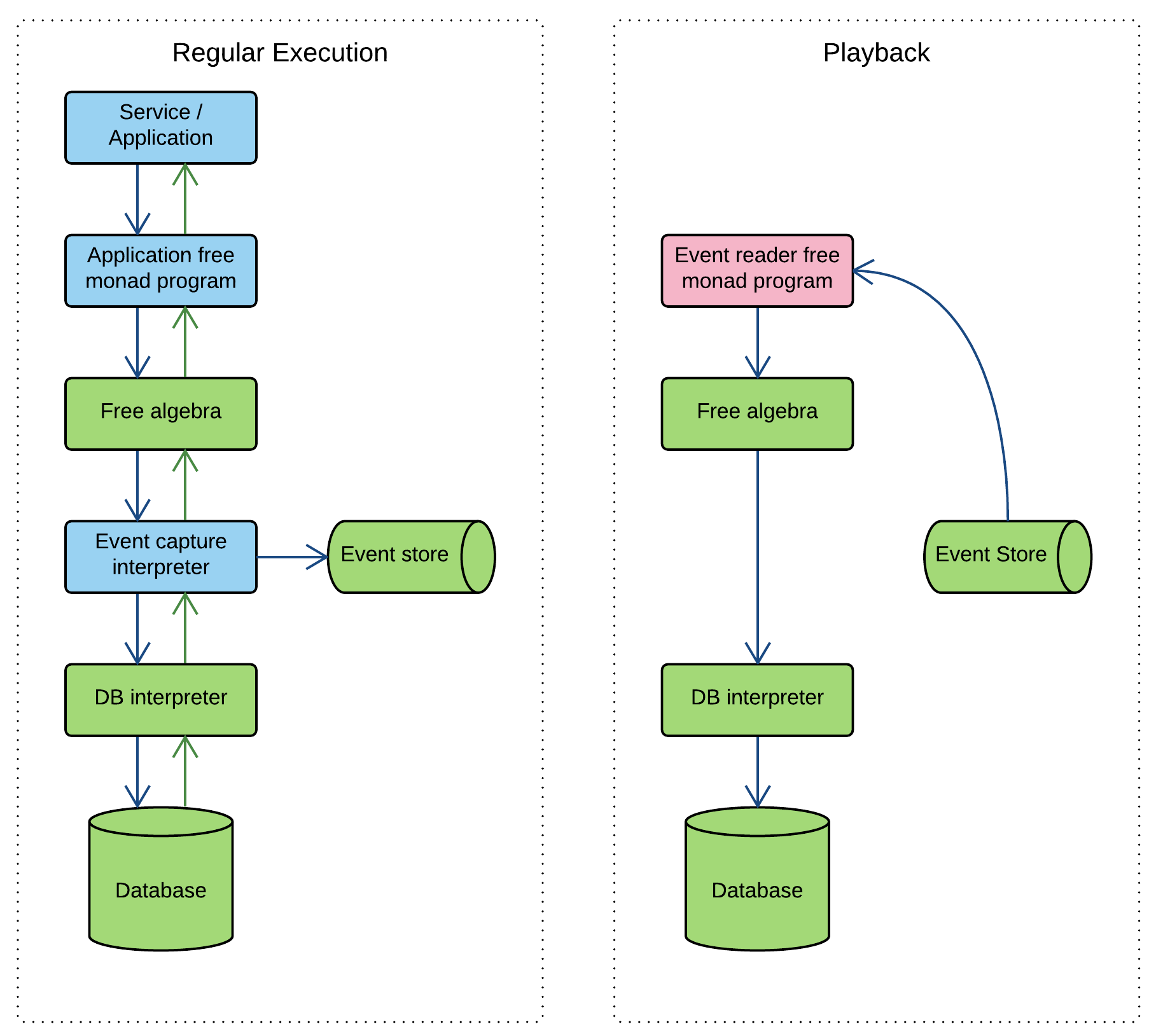

At this point the potential for adding event sourcing may start to become apparent. We just create an wrapper interpreter to capture the events before handing them on to the real interpreter.

final case class EventCapture[F[_], G[_]](interpreter: F ~> G) extends (F ~> G) {

override def apply[A](fa: F[A]): G[A] = {

publishEvent(fa)

interpreter.apply(fa)

}

}

and then we swap in this new interpreter:

val locationIO = program.foldMap(EventCapture(ShipOp2ConIO))

Here publishEvent does whatever we need it to do, writes it to a log in NoSQL database, publishes it to a Kafka queue, or whatever.

What makes it work so well is:

- The instructions or operations in

ShipOpare the very events we need to capture, and they are already nicely organised and available in data classes (specifically case classes in Scala) for serialisation. - The program has no need to even know that it is generating events for event sourcing capture. This is quite different from the imperative/OO case where there is quite a lot of ceremony

EventProcessorcode in the main program body. - Even the interpreter doesn’t need to know about event sourcing taking place. It just receives the event/instruction after its been logged, and processes it as normal.

Key to success is accurate replay of events. Ideally we want to write as little additional code as possible, and reuse whatever possible from the mechanism that was used to generate the events in the first place. The solution is beautifully simple - we take the stream of events, played from the beginning, or whatever the starting point is, and we transform this into a ShipFree instance, and then run this as we did with our original program. We could do this in a couple lines of code as follows:

val eventList = eventSteam.toList

val replayProgram = eventList.traverse[ShipFree, Unit](_.liftF.map(_ => ()))

Then we run replayProgram exactly as before. It may work slightly differently in production code; e.g. we may split the replay operation into batches, but it would work this way in principle.

Designing event sourceable algebras

There are some issues regarding the design of algebras still to deal with. There are restrictions on the algebras themselves required to make them event sourceable. These specifically relate the the CQRS requirement - separating commands from queries. The most important of these is that all event details for the events we are capturing need to be exogenously speficied. This immediately rules out database generated record IDs.

For example if we modified our algebra as follows:

object ShipOp {

...

case class AddShip(name: String, code: ShipCode) extends ShipOp[ShipCode]

...

}

and our program becames:

val program: ShipFree[_] = for {

...

krCode <- AddShip("King Roy", ShipCode.kr).liftF

_ <- Departure(krCode, PortCode.sf).liftF

...

In this case we rely on the database to generate a code or ID for the ship. It’s immediately clear that this won’t work for event sourcing. When we replay our event stream, the AddShip instruction will potentially return a new code/ID, and that will invalidate the Departure event that follows, as this event will be replayed with the old ID.

It’s not a coincidence that the AddShip instruction violates CQRS - it involves a state mutation (inserting), which makes it a command, but it also returns an ID for later consumption, that makes it a query as well.

There are potential mechanisms that could be constructed to manage this, but they are far more complex than designing the algebra to avoid this scenario in the first places. It also means that all record IDs that we may need to reference must be either:

- IDs that are sourced externally, that we know are not going to change, or may change in a way that can be managed. For example we don’t expect stock ticker symbols to change too often, though they are known to change with certain corporate actions.

- Randomly generated IDs - typically

UUIDs - that have a negligible collision probability.

Some database implementations we may use don’t support creating records with an externally specified ID. In these cases, we have no option but to involve a lookup table, but this needs to be an implementation detail opaque to the algebra / program. This may add some small performance overhead, but the benefits in most cases of an event sourcing archtecture will far outweigh this.

As a consequence of this segregation of commands and queries, you may note that all the commands in our algebra have uninteresting return types. These would typically be such as:

Unit- no return status.Boolean- denoting success or failure.Int- denoting how many records were affected, if the operation may affect several records.

You will immediately be able to identify any queries by their more interesting return types.

A further condition we would like our implementation to satisfy is idempotence. If an insert fails first time, it may be necessary to retry, so we may end up with a repeated event. We don’t want the replay mechanism to have to care about what these events returned first time around, but rather just accept that we may end up repeating the replay action, and not have to care about it.

Yet another important requirement for our algebra is that it must not leak any details of the underlying implementation. This means we want to keep our data types for both input and output to language primitives, simple serialisable data types such as case classes and standard collection data types like List etc. We definitely want to avoid for example, something like a Vertex datatype creeping into our algebra just because the underlying implementation happens to be a graph database.

Achieving better command / query separation

Of course from an event sourcing point of view, we don’t necessarily want to log our queries. We certainly want to ignore the queries when replaying the event history to recreate the database. We therefore identify two strategies for achieving this.

Here’s a quick and dirty strategy to do this that will get the job done. We modify our algebra as follows:

sealed trait ShipOp[A]

sealed trait ShipCommandOp[A] extends ShipOp[A]

sealed trait ShipQueryOp[A] extends ShipOp[A]

object ShipOp {

// Commands

case class AddPort(name: String, code: PortCode) extends ShipCommandOp[Unit]

...

// Queries

case class GetLocation(ship: ShipCode): extends ShipQueryOp[Location]

...

}

Then modify our event capture as follows:

final case class CommandCapture[F[_], G[_]](interpreter: F ~> G) extends (F ~> G) {

override def apply[A](fa: F[A]): G[A] = {

fa match {

case _: ShipCommandOp[_] => publishEvent(fa)

case _: ShipQueryOp[_] => ()

}

interpreter.apply(fa)

}

}

But we can improve on this. A better solution is to split the algebras completely into separate algebras with their own interpreters.

sealed trait ShipCommandOp[A]

sealed trait ShipQueryOp[A]

object ShipCommandOp {

case class AddPort(name: String, code: PortCode) extends ShipCommandOp[Unit]

...

}

object ShipQueryOp {

case class GetLocation(ship: ShipCode): extends ShipQueryOp[Location]

...

}

Then we create a separate interpreters for these algebras:

object ShipCommandOp2ConIO extends (ShipCommandOp ~> ConnectionIO) {

override def apply[A](fa: ShipCommandOp[A]): ConnectionIO[A] = fa match {

case ... // only handle the commands

}

}

object ShipQueryOp2ConIO extends (ShipQueryOp ~> ConnectionIO) {

override def apply[A](fa: ShipQueryOp[A]): ConnectionIO[A] = fa match {

case ... // only handle the queries

}

}

and we only wrap the ShipCommandOp2ConIO interpreter with our original EventCapture interpreter.

So we have achieved full CQRS. But does this mean that we can’t include commands and queries in the same program? Fortunately it doesn’t. We can create the coproduct algebra of the command and query algebras:

import cats.data.Coproduct

type ShipOp[A] = Coproduct[ShipCommandOp, ShipQueryOp, A]

Returning once again to our vector space analogy, a coproduct is the equivalent of creating combining two sets of basis vectors of the same dimension with linearly independent vectors, and then Free[ShipOp, A] is analogous to the vector space generated by this combined basis set.

We need to make a slight modification to the program. Instead of lifting our instructions into the Free[ShipCommandOp, A] or Free[ShipQueryOp, A] as before with .liftF, we need to lift instructions into the wider Free[ShipOp, A] monad as follows:

val program: ShipFree[_] = for {

_ <- AddPlace("Los Angeles", PortCode.la).inject[ShipOp]

_ <- AddPlace("San Francisco", PortCode.sfo).inject[ShipOp]

_ <- AddShip("King Roy", ShipCode.kr).inject[ShipOp]

...

_ <- Departure(ShipCode.kr, PortCode.sf).inject[ShipOp]

...

_ <- Arrival(ShipCode.kr, PortCode.la).inject[ShipOp]

location <- GetLocation(ShipCode.kr)

} yield location

Slightly more busy, but still perfectly manageable and elegant enough. So where do these .liftF and .inject come from? Well, to make things nice and easy, here’s a simple helper trait that provides these. It can be used for any free monad algebra.

import cats.free.{Free, Inject}

trait FreeOp[F[_], A] { this: F[A] =>

def liftF: Free[F, A] = Free.liftF(this)

def inject[G[_]](implicit I: Inject[F, G]): Free[G, A] = Free.inject(this)

}

Here we use the Free object of the cats library, which also provides the liftF and inject methods that lift the operation into its free monad and the coproduct free monad respectively. It also provides the necessary instance of the Inject type class needed for the coproduct.

We just need to inherit from this base class to get these methods. Our algebras becomes:

sealed trait ShipCommandOp[A] extends FreeOp[ShipCommandOp, A]

sealed trait ShipQueryOp[A] extends FreeOp[ShipQueryOp, A]

type ShipOp[A] = Coproduct[ShipCommandOp, ShipQueryOp, A]

We probably could have done the same thing with an implicit class, but this works nicely enough.

Now we can simplify the CommandCapture interpreter:

final case class CommandCapture[F[_], G[_]](interpreter: F ~> G) extends (F ~> G) {

override def apply[A](fa: F[A]): G[A] = {

publishEvent(fa)

interpreter.apply(fa)

}

}

Finally we need an interpreter that can interpret both command and query instructions in the coproduct ShipOp instruction set. Fortunately this is really easy with the or method of the natural transformation ~>[F[_], G[_]] type class, and we end up with:

val ShipOp2ConIO = CommandCapture(ShipCommandOp2ConIO) or ShipQueryOp2ConIO

and we run our program with program.foldMap(ShipOp2ConIO) exactly as before. Note that we only wrap the command interpreter with the event capture wrapper.

With this architecture, we have decoupled commands from queries completely. Certain use cases, such as event playback, don’t need to know about the queries at all, neither the algebra nor the interpreter. Other use cases, such as a web API, may need to know about both, and for this, we can easily form the coproduct and use them simultaneously.

Our event capture interpreter implementation here is quite naive, and has some significant shortcomings. Thanks to my colleague Marek Kadek for pointing this out. Based on some really fruitful conversations we have come up with a better implementation that addresses these shortcomings. There’s quite a lot to say about this, both in terms of what these shortcomings are and their resolution, so rather than address it here, it will be discussed in the follow-up post Free monad event sourcing interpreters.

Well that’s it for now - I hope this inpires someone to use free monads to implement event sourcing, or if you’re already using free monads, that you decide to take advantage of the (almost) free event sourcing it enables. It’s really marvellous stuff, not hard to get enthusiastic about!